4-way FS team Chimera share their tips on using tunnel as a training aid for your outdoor season

One of the downsides to being a British team is that the British weather is a little… err… unpredictable Luckily, with wind tunnels up and down the country, we’re able to make use of these handy training aids to hone our skills and almost make up for the challenging outdoor conditions we often face here in the UK.

But while tunnel flying has developed as a whole new sport in itself, it’s important to pay attention to the fact that, when used as a sky support, the tunnel is a tool to help us get better outdoors. Training as an outdoor team indoors is, in many ways, quite different to training as an indoor team indoors. Allow us to explain…

The many benefits of indoor skydiving

It’s weird to think that, pre-2005, we didn’t even have wind tunnels here in the UK. Indeed, many of today’s skydivers will remember a time when indoor skydiving wasn’t even a thing, while those people just joining our sport will undoubtedly wonder how we managed without it!

When we fly in the wind tunnel, we take advantage of a range of benefits. For one, the time we’re able to fly for is far more than we’d get even in a full day’s heavy outdoor training, with many teams opting to fly anywhere between 30 minutes to a few hours

of tunnel flying over the course of an indoor camp. That means that, rather than having to go up in the plane, do our 60 seconds, get down, go up again, do another 60 seconds and so on, we get solid time dedicated solely to the “freefall” part of our jump.

Then, there’s the ability to debrief in the moment. Your coach can be there watching you in real time in the tunnel, providing feedback mid-flight and quick debriefs between flights so you’ve got that immediate knowledge of what you can do better and where you need to improve.

The reference points we have in the tunnel are also really valuable (though potentially hazardous too, as we’ll come on to soon). In the sky, we don’t know how we’re moving around, whether it’s the piece or the spinner that’s missed their mark, or even how our levels are changing through the jump. In the tunnel, you see everything and a combination of top-down and on-level footage will reveal plenty of areas for improvement that would be difficult to capture when thousands of feet up.

Translating tunnel to sky

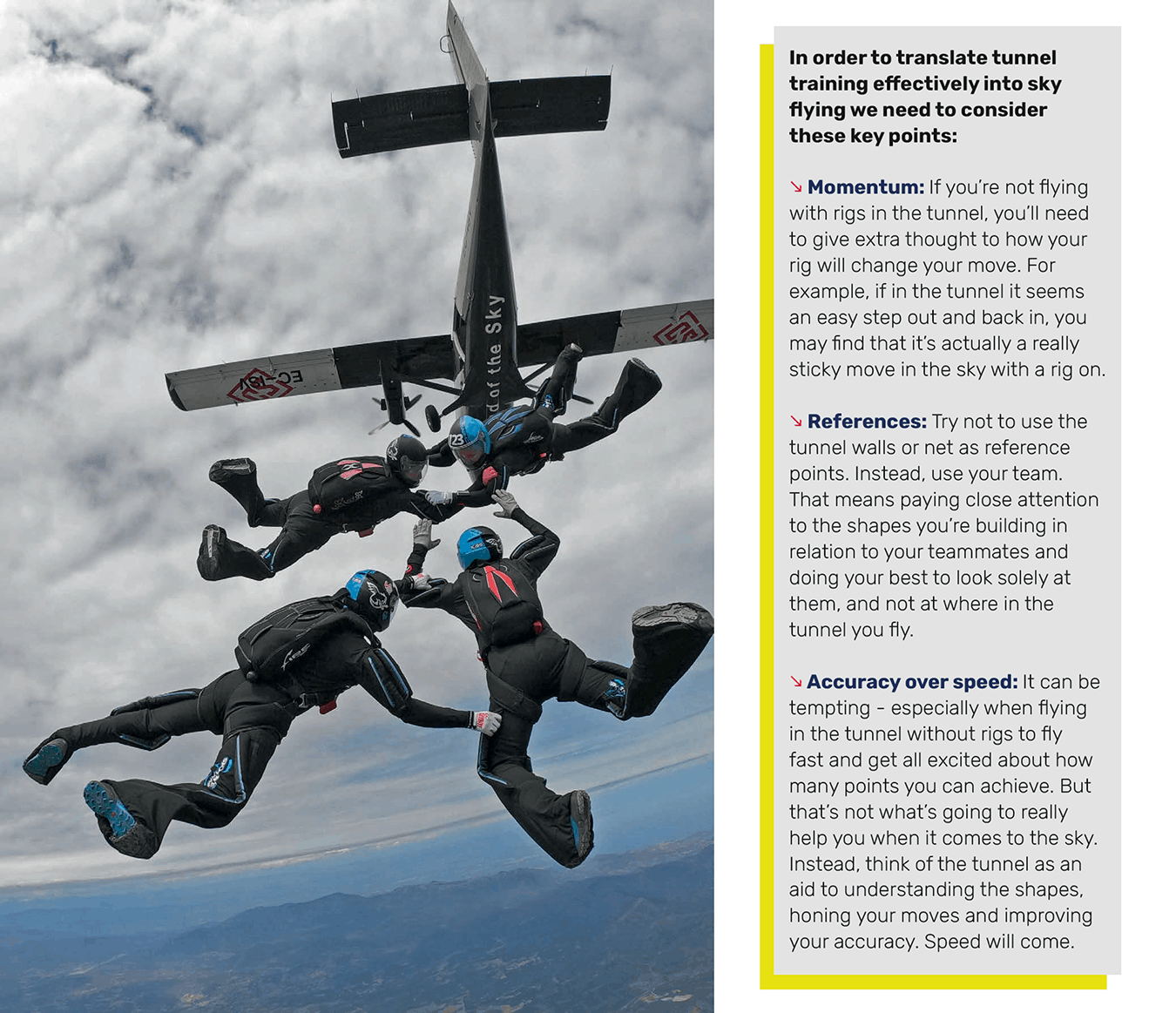

Though there are certainly many benefits to tunnel flying, there’s also plenty to consider when using it as a training aid for the sky.

For one thing, we often fly in the tunnel without rigs, but in the sky inevitably have to put them on. That immediately changes our weight, our shape and our momentum. Flying without rigs in the tunnel is, even for flat flyers, a whole different beast to outdoor flight and that makes a difference.

Those reference points we talked about earlier also warrant additional consideration. It is, absolutely, a benefit of the tunnel that we can see how our team is moving about and work toward tighter, more efficient flying. But at the same time, we cannot rely on the tunnel references, the main one being the walls and the net, because those references are no longer there for us when we get into the sky.

A third of your jumps can’t be trained in the tunnel

Of course the major, overriding difference between the tunnel and the sky is that skydiving involves jumping out of a plane, while tunnel flying, obviously, does not.

Competition working time is just 35 seconds for 4-way. Given that we’re on the hill for maybe ten seconds of our jump, and that the exit from the aircraft has such a huge bearing on how quickly we can start turning points, that’s potentially a third of your skydive that you can only train outdoors. That’s a big old chunk!

For us, that means we simply have to dedicate some of our resources to outdoor training, whether it’s here in the UK or going overseas to somewhere where the weather is a little more predictable to ensure we get the jumps in. We’ve even committed some jumps to low altitude, allowing us to see the exit and hill and not much else but meaning we can do higher volumes of 7,000ft jumps to balance out the ratio of tunnel to outdoor training.

Tunnel phase to vs jump phase

How you manage tunnel training will depend entirely on your team. For us, we’ve always structured our year with a tunnel phase and a jump phase, with the break point usually being the World Challenge indoor competition (which also served as the British Indoor Nationals in 2019).

During our tunnel phase, we focus on tunnel training without rigs. We look at where we are at the beginning of the season and here our focus needs to be in order to improve, and we work on that. For example, in our earlier years we focused on block technique more than anything, whereas we had a big focus on random efficiency in 2019. We do it without rigs because we’re looking at shapes and techniques, pinning down the technical side and not thinking too much about speed.

Of course, tunnel competitions mean that we also spend some of this time practicing our tunnel entrances and getting ourselves to a good pace – but as an outdoor team, our primary focus is always on using the tunnel as a way to get the technical elements down.

During the jump phase, we’ll focus more on jumping and tend to do less tunnel time than we do in the tunnel phase. When we do go to the tunnel, we wear rigs to do so, which means we’re able to concentrate more on things like momentum. We use the tunnel even more as a means for rehearsing the moves we need to improve in the sky, so if our block 12 needs a slight adaptation, or if we’ve had a sticky move from a 14 to an eight, let’s say, we’ll take it into the tunnel and iron out any issues there before repeating in the air.

The bottom line is that tunnel is an excellent tool for any kind of flyer to develop their skills, whether you’re in an FS team, learning a new skill or brand new to the sport.

If you’d like any help preparing your team for competition or if you want to follow more on how we do it this season, check out our Facebook page at http://facebook.com/chimeraskydive

Words: Chimera

Photos: Chris Cook

First published in the February 2020 issue of Skydive the Mag.

First published in the February 2020 issue of Skydive the Mag.