The First British (and European and Commonwealth) 8-Way Star

Mark Miller, May 2013

On the 17th of October 1965 the Arvin Good Guys, as they subsequently called themselves, made the first 8-way star in the world at the Arvin Drop Zone in California, USA. It was photographed in free-fall by Bob Buquor. Not long afterwards he drowned while filming skydiving for a Hollywood movie. Bill Newell, no.8 of that original group and friend of Buquor started an award scheme for skydivers who had achieved an eight way star, as a memorial in Bob’s name. The star had to be held for five seconds to count.

California had the weather and planes and US surplus parachute equipment was cheap and accessible. Jumpers from the US and outside felt the need to get there and join in the star making in that glorious weather which they didn’t have at home. It was California Shit or Bust, rather like the Okies in the Grapes of Wrath!

British jumper John Beard made it there in 1969 and got his SCR Patch (Star Crest Recipient Badge). It was much coveted on his return home. Until that time the largest star in the UK had been a 5-way at Thruxton in 1967 out of their Rapide, a nine place aircraft, and skills had been increasing. But the parachute club at Thruxton had closed and growth of controlled airspace around London had restricted altitude at other drop zones. There was a drastic shortage of aircraft and altitude for a couple of years as far as star making was concerned.

Then in 1969 the Shorts Skyvan of South West Aviation at Exeter came on the scene. It was available some weekends and could be flown into Dunkeswell only a short distance away. With a wide tailgate exit, closed until jump-run for comfort, fast climbing with seats for 15 jumpers, it easily achieved 12-15000 ft on run-in and jumps cost typically just over £1 each – cheap at the time even allowing for inflation! This was sheer heaven : 6 jumps a day in good weather.

John Beard got things moving and invitations were sent out to all those experienced jumpers in the country who it was thought could contribute to making a large star. ‘Auditions’ were held with full Skyvan loads from 12 grand plus, but very little came of it. Despite the large tailgate, exits were slow and long vertical gaps generated high speed approaches with frightening closure rates. The stars didn’t get much beyond a 4-way with plenty of funnels. It became clear that techniques and disciplines had to be learnt or there would be no 8-way star.

By 1970 400 SCRs had been awarded, all in the USA, and their largest star was up to a 20-way. British jumpers were feeling the pressure to achieve what they were sure was within their reach. A group formed around John Beard and other of those previously successful Thruxton jumpers – John Harrison, Terry Hagan and Jim Crocker. They were joined by Mike O’Brien, Tony Unwin, Guy Sutton and John Shankland, and they all had become members of the Greenjackets Regiment Territorial Army Display Team, which had been going for some time. The average number of jumps of this group was nearly 600. They knew they had the ability and experience and decided to stick at it until they got the eight.

It was known that the heavier guys needed to be in the base, because the formation fell slower as it grew and the lighter guys could easily stay with it. Round the other way the heavier guys might go irretrievably below because they all wore the same jumpsuit, the twin-zip Pioneer number, even though there were significant differences in fall rates. Subsequent years saw a revolution in jumpsuit designs and modifications. The typical rig then was a surplus or surplus style sage green pack and harness, front and back or piggyback in similar style. Paracommanders were the universal round main parachute and harnesses used unnecessary and heavy hardware with one and a half shot capewells. Main ripcords released sprung pilot chutes. Reserves were 24ft flat circular, or 26ft conical if you were well heeled. ‘Paraboots’ with thick soles were worn by everyone and thought essential. Trainers were just over the horizon! Altimeters were heavy aircraft surplus “ICANS” attached to the chest strap with a jubilee clip, door hinge and wing nut and bolt. The resultant jumper carried a considerable weight.

In freefall it was realised that the formation must be held level as it formed or it would slide across the sky as a moving target, and it must be stopped from rotating or the slots would be hard to get into. All obvious stuff, but it had to be learnt by experience. Individuals flying over or under the formation could easily cause a funnel, and did. When someone broke wrists to get into the star they had to shake up and down positively as a signal or the grip would be released before the entrant had hold, and the star would fly open.

Debriefs after the jump were important to find out what went wrong, and right. This was a new thing and a new discipline in itself – finding out the truth of the mishaps despite the embarrassments and the pressure to just get packed and up again. Portable video for a freefall cameraman was ahead in the 1980s. Polaroid Super-8 cine was first used in 1979 by Symbiosis 4-way. John Harrison was the most experienced formation flyer and he provided the leadership, coaching and calming influence in the group.

The Skyvan weekends continued with the usual British weather problems. John Beard made a connection with ITN News who agreed to follow the possibility of a British record being achieved. A freefall cine cameraman, Mark Miller, was taken on to follow out all the dives and ITN provided 16mm cine film and developed it so that the eventual 8-way could be shown on the News. On the 6th September 1970 an 8-way was achieved, but it only lasted for 2-3 seconds so was discounted. It had to be five.

Then in the following week the Royal Navy at RNAS Culdrose in Cornwall provided two Wessex helicopters for a few days. Being in the TA was paying off! Miller wasn’t in but he pretended to be.The team was joined by Charles Shea-Simonds as stills photographer. He’d taken good pictures of those 4 and 5 ways at Thruxton and much besides. The Navy provided great food and accommodation at Culdrose but Cornwall was socked in. The team flew up to Bodmin Moor and landed there – still a solid low base. Up to Dunkeswell in the chopper and the same again there. Flying back to Culdrose at low level along the coast with the door open was good fun though. Eventually on the last day it was jumpable at Dunkeswell and the team made 6 jumps. Of course the chopper exit and dive angle was completely different and took some adjusting to. The weather turned cloudy and the best that could be achieved that day through layers of cloud was a 6-way.

Four miles east of Dunkeswell on the Blackdown Hills is the disused wartime airfield of Upottery with it’s 3 large concrete runways (now better known as the D-Day launch point for the “Band of Brothers” Easy Company of the American 101st Airborne Division). Above cloud on the run-in, if Dunkeswell itself was not in sight, the team and John Beard as spotter, would be reassured by the sight of Upottery. In fact if the jumpers actually landed there no one seemed to mind, and a lift could soon be hitched back if you were obviously carrying a parachute. This was the West Country! On this last chopper jump of the day, John couldn’t actually see Dunkeswell or Upottery but gave the required reassurance to the guys as they got out saying: “It’s Upottereeeee…”. On landing Jim Crocker spoke to a local:

Jim: “Where’s the airfield?”

Local: “What airfield?”

Jim: “Dunkeswell”

Local: “Where be Dunkeswell?”

Jim: “Near Honiton”

Local: “Oniton? Oniton be in Devon. You be in Somerzet!”

They’d landed 20 miles from Dunkeswell so the chopper landed and took some of them back while others struggled back by road. Worst ‘spot’ ever.

It was a month to the next Skyvan weekend at Dunkeswell, the 17/18th October, quite possibly the last opportunity that year for decent weather. So clear blue skies and nil wind all day on the 17th were most welcome.

John Beard would spot the aircraft from the pilot’s window initially and then signal Shanks to open the tailgate on the run-in, keeping the cold out as long as possible. A jumpship with an in-flight door was a complete novelty. Then John would finish spotting at the tailgate and out they would go in pairs, with Shanks and John always the reliable quick base and pin. Shanksy must have been looking forward to that eight more than most – tired of being baseman. The two cameramen exited as the last pair.

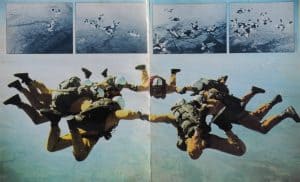

The first jump was a 7 that broke up as the 8th made contact. The second was a humble 5. It was the third that did it. Guy in 3rd, star slides and rotates 180. Jim chases and in 4th, while Terry whizzes underneath,…phew!, it’s still intact. Mike gets in 5th and Tony quickly 6th. Terry’s back up the other side and in nicely 7th, followed by John H 8th. It’s there, it’s really there!

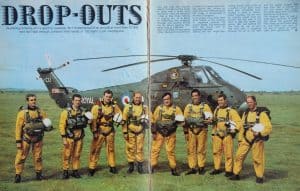

Both cameramen’s Newton Ring Sights have been patiently homed in and now they’re really buzzing too. We wanted everyone to see this as well as possible and prove it lasted… 7 seconds, ‘till break-off time. Big wave-off from Shanksy. Canopies open right overhead the packing area; there’s everyone yelling and whooping and spiralling all the way down. It’s one of those jumps that feels so good that the adrenalin seems to last well into the next week at work. And didn’t the beer taste good that evening at the Royal Oak down in the village! The team photo beside the Skyvan later that afternoon shows the pilot and a jumper on top of the aircraft refuelling it from barrels, and the guys left to right: John Harrison, Tony Unwin, Terry Hagan, Jim Crocker,Mike O’Brien, Guy Sutton, John Beard and John Shankland. Photographers kneeling: Charles Shea-Simonds (stills) and Mark Miller (cine). It had taken 31 team jumps to achieve that eight.

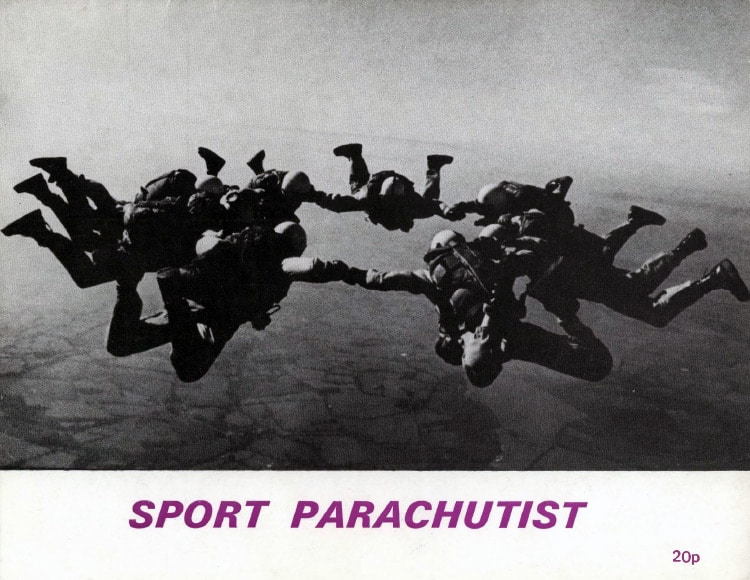

Charlie’s picture of the eight went on the next cover of Sport Parachutist together with his story inside, and Mark’s film went out on the ITN News. The next year Skyvan jumping continued at Dunkeswell , Yeovilton and Weston on the Green. There was a first 9, 10, 11 and 12 with an influx of new jumpers.The Greenjackets Team split into two groups forming the core of two 10-way speed star teams. Rivalry between them was intense. We learnt how to get through aircraft doors fast and practised it a lot. Those lazy Skyvan exits seemed odd looking back. By 1973 that Skyvan had gone but a Twin Pioneer at Staverton, Cheltenham, was carrying both teams up on alternate lifts. A competition had to decide which team would represent GB at the First World Cup for Relative Work (FS) in the USA. The first 10-way speed star competition at Stoke Orchard, a grass field near Staverton where the Twin Pin could land, was the venue for the fiercest competition you could imagine. But that is another story.